Wars, threats of wars, and perceived risks to national security have prompted the government to, at times, restrict freedom of speech and other First Amendment freedoms. In this Thursday, Sept. 27, 2001 file photo, U.S. Attorney General John Ashcroft meets with reporters at FBI headquarters in Washington, where he released photographs of the 19 suspected hijackers. In the wake of 9/11, he was the administration's prime advocate of the USA PATRIOT Act, which gave the government broad powers to investigate and prosecute those suspected of terrorism. (AP Photo/Joe Marquette)

Despite the absolute language of the First Amendment, wars, threats of wars, and perceived risks to national security have prompted the government to, at times, restrict freedom of speech and other First Amendment freedoms throughout U.S. history.

A prime example is legislation passed only seven years after the adoption of the Bill of Rights, including the First Amendment. In 1798 the Federalist Congress, fearful of an impending, full-blown war with France, adopted the Sedition Act, which attempted to stifle any speech that criticized the president, who was conducting an undeclared conflict with France at sea.

The Federalist Party justified the Sedition Act as a measure needed to prevent threats to national security from within the country.

During the Civil War, the federal government restricted freedom of speech and freedom of the press. Union generals took measures to prevent newspapers from publishing battle plans and to keep Confederate sympathizers from aiding the enemy by disseminating military information or discouraging enlistments. Throughout the war, newspaper reporters and editors were arrested without due process for opposing the draft, discouraging enlistments in the Union army, or even criticizing the income tax.

Likewise, Southern states adopted laws that limited the freedom of speech with regard to abolitionist sentiment.

World War I saw the adoption of the Espionage Act of 1917 and the Sedition Act of 1918. These laws led to the first Supreme Court decisions on when national security could justify infringing on First Amendment freedoms. Punishments against political dissidents were upheld in Schenck v. United States (1919) and Abrams v. United States (1919) because the Court found that their speech presented a clear and present danger to national security and war efforts.

World War II and the Cold War that followed spurred adoption of the Smith Act that made it illegal to call for the overthrow of the U.S. government, intrusive congressional investigations into personal beliefs and associations and other efforts to suppress domestic Communism.

For example, in 1950 Congress passed the McCarran Internal Security Act, which defined a “Communist-action organization” as an instrument for overthrowing governments and required the Communist Party of the United States to register with the attorney general. Registration required that the party provide a list of all its current members. In 1961, the Supreme Court upheld the law on the basis of national security interests. Only one justice, Hugo Black, dissented on grounds that registration violated First Amendment protections of freedom of association.

Opposition to U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War resulted in multiple Supreme Court cases regarding free speech, including cases involving symbolic speech. In one case, the Supreme Court upheld the conviction of man who burned a draft card. In another, it upheld the rights of students to wear black armbands to school in protest of the war.

While recognizing that national security may justify restrictions on First Amendment rights, the Court has also set limits.

In this June 21, 1971 file photo, Katharine Graham, left, publisher of The Washington Post, and Ben Bradlee, executive editor of The Washington Post, leave U.S. District Court in Washington after getting the go-ahead to print the Pentagon papers on Vietnam. (AP Photo/File)

In the landmark free press decision Near v. Minnesota (1931), the Court established a general rule against prior restraints on expression. However, the Court noted that the government could shut down a newspaper if it published military secrets: “No one would question but that a government might prevent actual obstruction to its recruiting service or the publication of the sailing dates of transports or the number and location of troops.”

Nevertheless, the government must provide proof that national security interests really are in play — that is, the government cannot simply use national security as a blank check to sidestep constitutional challenges.

In New York Times Co. v. United States (1971), the majority of the Court rejected the government’s national security justifications for attempting to prevent the New York Times and the Washington Post from publishing the Pentagon Papers, the classified history of the U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War. In his concurring opinion, Justice Hugo L. Black explained that “the word ‘security’ is a broad, vague generality whose contours should not be invoked to abrogate the fundamental law embodied in the First Amendment.”

The “War on Terror” after the Sept. 11 attacks on the United States brought a new focus on the proper balance between liberty and national security. Controversy arose over provisions in the new USA Patriot Act, especially provisions that gave the FBI increased power to probe into a person’s communications through the use of “national security letters” (NSLs).

A national security letter is an administrative subpoena instrument used by the FBI to compel recipients of the letter to comply with requests for various data and records of the person who is the subject of the subpoena. This instrument requires no probable cause or judicial oversight. It also contains a gag order preventing recipients from acknowledging they have received a letter. A 2007 Department of Justice audit revealed that in 2005, 47,221 requests applicable to 18,000 people were issued. Similar numbers were posted for 2003 and 2004.

Yet another national security issue that continues to generate controversy is the published “outings” of known intelligence operatives. The best-known case is that of career CIA operative Philip Agee.

The outing of Valerie Plame as a nonofficial CIA operative, seen here testifying before Congress, resulted in the prosecution of I. Lewis “Scooter” Libby who shared her name with the press. Libby ultimately was not convicted under the law that makes it a crime to reveal secret government agents, but under perjury and obstruction of justice charges. (AP Photo/Susan Walsh)

Agee served in Latin America but became disaffected by the CIA’s role there. He left the agency in 1968, a self-avowed socialist. In the 1970s, Agee published Inside the Company in which he named over 250 operatives and assets for the CIA in Latin America. In 1974 he announced a campaign against the CIA.

In response to Agee’s activities, Secretary of State Alexander M. Haig Jr. revoked Agee’s passport. Agee countered by charging that his right to criticize the government under the First Amendment had been infringed by Secretary Haig’s action. In its 7-2 decision in Haig v. Agee (1981), written by Chief Justice Warren E. Burger, the Supreme Court disagreed. Justices William J. Brennan Jr. and Thurgood Marshall dissented.

The Intelligence Identities Protection Act (IIPA) of 1982 was passed in the wake of the disclosures made in part by Agee and by the assassination of CIA Station Chief Richard Welch by the Greek terrorist group after his identity was revealed in the magazine Counter-Spy. The law makes it a federal crime for those with access to classified information to intentionally reveal the identity of an agent whom one knows to be in or was recently in certain covert roles with a U.S. intelligence agency.

The law has been used against CIA operative Sharon Scranage and against I. Lewis “Scooter” Libby, a former chief of staff to Vice President Dick Cheney.

Libby was indicted under the IIPA for revealing to journalists that Valerie Plame, the wife of a critic of the Bush Administration, was a nonofficial cover operative of the CIA. Journalists published the information. Ultimately, Libby was convicted for perjury and obstruction of justice, but not convicted under the IIPA.

More recently, the military community and the U.S. Department of Homeland Security have become concerned about disinformation campaigns in America by Russia, China and Iran. These campaigns involve disguised accounts on social media platforms such as Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and YouTube to spread false information intended to undermine the stability of the United States.

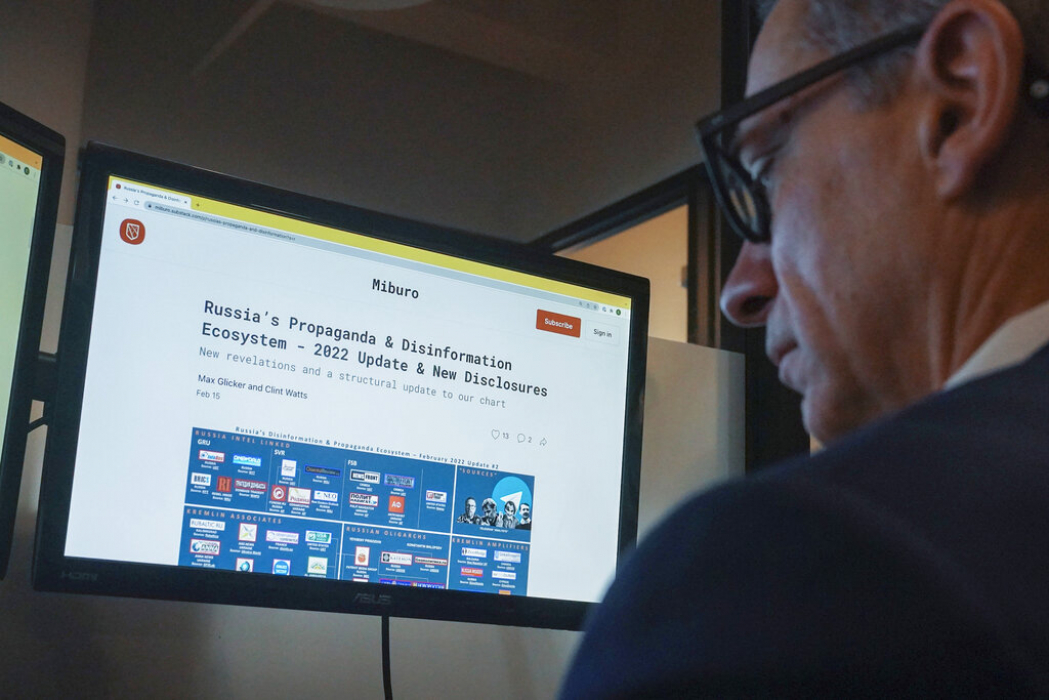

Clint Watts, president of Miburo, a research firm that tracks foreign disinformation operations, works at his desktop at company headquarters, on March 15, 2022, in New York. Some consider these disinformation campaigns a national security threat. (AP Photo/Bebeto Matthews)

For example, the U.S. Department of Justice’s Cyber Digital Task Force, established by then-Attorney General Jeff Sessions, said in a 2018 report that Russia’s covert disinformation campaign in the United States is intended to “sow division in our society, undermine confidence in democratic institutions, and otherwise affect political sentiment and public discourse to achieve strategic geopolitical objections.”

However, the establishment of a Disinformation Governance Board in 2022 to guide the U.S. Department of Homeland Security on addressing disinformation that threatened the national security of the United States was quickly disbanded after its received public criticism.

Some portrayed the board as an Orwellian tool that could infringe on privacy and free speech rights. They likened it to the fictional “Ministry of Truth,” a propaganda machine that controlled information for Oceania citizens in George Orwell’s dystopian book, “1984.”

This article was published in 2009 and updated by Deborah Fisher in 2023. Fisher is director of the John Seigenthaler Chair of Excellence in First Amendment Studies at Middle Tennessee State University.

While the board’s quick dissolution illustrates fear of government control of information and censorship, others are concerned that malicious foreign actors have taken advantage of American speech rights in a new “information warfare” that allows them to avoid direct military confrontation to achieve their goals.

This article was originally published in 2009 and updated by Deborah Fisher in 2023. Fisher is director of the John Seigenthaler Chair of Excellence in First Amendment Studies at Middle Tennessee State University.